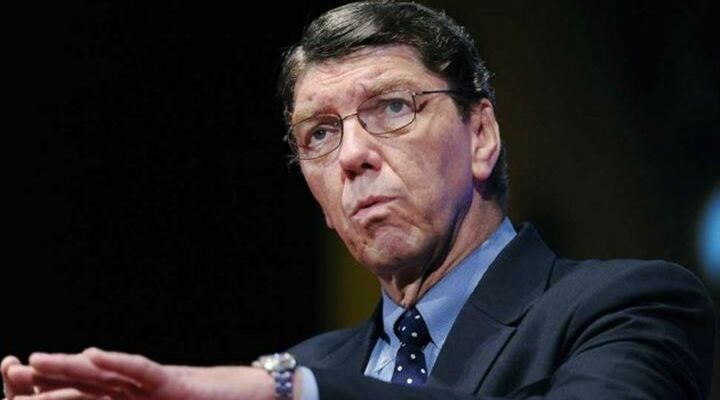

Harvard Business School professor and businessman, Clayton Christensen, known by many as the “godfather” of disruptive innovation, died in January at the age of 67.

“Why do so many great companies fail?” Professor Christensen asked during one of his doctoral seminars. I was one of the dozens of wide-eyed first-year students in the class who aspired to become a business school professor one day but had no idea how businesses actually worked.

“The puzzle that I was trying to understand,” he continued, “was that most companies that are widely regarded as unassailable are found, a decade or two later, in the middle of the pack or at the bottom of the heap. But man, I know a lot of CEOs, and many are very smart for a very long time. At the height of their corporate success, they are praised for their intelligence. When the firm falls, they are blamed for their stupidity. But I don’t believe people’s intelligence swings that much.”

“So, the puzzle was” — he gazed at the blackboard and picked up a piece of chalk — “how is it that even the smartest people find success so hard to sustain?” That truly was the innovator’s dilemma: “Doing the right thing” would kill you.

More than 20 years after The Innovator’s Dilemma was published in 1997, many large companies are still obsessed with doing the right thing: They need to listen to their customers; they need to invest aggressively in new technologies to provide their customers with more and better products; they need to carefully study the market trends and systematically allocate investment capital to the innovations that promise the best returns. And, ironically, because they do exactly all the above, these well-run companies are predestined to lose their market positions to other upstart disruptors.

In Clay’s days (we will soon learn to call Clayton Christensen “Clay”), companies that experienced epic failure included RCA, which struggled against Sony; NCR, which struggled against Digital; Seagate, which struggled against SanDisk; and Harley-Davidson, which struggled against Honda. Today, the pattern features Walmart against Amazon, Gillette against Harry’s, BMW against Tesla, HSBC against Revolut, and Merrill Lynch against Betterment. The actors change, but the story remains.

Here is how RCA died. When RCA first discovered transistor technology, it was already the market leader in colour televisions produced with vacuum tubes. The company had little use for the transistor beyond treating it as an engineering novelty. It decided to license the technology to a little-known Japanese firm called Sony.

Sony could not build a TV out of transistors, but it did manage to produce the first transistor radio. The sound quality was awful, but teenagers, who were delighted to get the freedom to listen to rock music away from their parents’ complaints, loved the radio. Transistor radios took off. Still, the profit margins were so low that RCA saw no reason to invest further. It was busy making serious money and investing every R&D dollar to improve vacuum tube colour TV.

Meanwhile, Sony was looking for the next big thing. It launched a portable, low-end, black-and-white TV at a rock-bottom price, targeting low-income individuals. Called the “Tummy Television”, it was tiny enough to perch on one’s stomach — the antithesis of RCA’s centerpiece designed for middle-class families. Why would RCA invest in transistors to make an inferior television for a less attractive market? It did not.

Unhurried, but without wasting a minute, Sony steadily improved the transistor’s performance until it produced the first colour TV based entirely on the new technology. Overnight, RCA found itself trying to catch up on a technology that it had pioneered but chosen to license out and then ignored for three decades. Clay called this type of technology — inferior at first but immensely useful later — disruptive. The term has since been immortalised in the business lexicon and preached throughout Silicon Valley.

Clay went on to elaborate his theory, writing case books; predicting industry outlooks; investigating healthcare, K-12 education, and higher education. He analysed the causes of a nation’s prosperity, and ultimately examining life and its meaning. He founded a consulting firm — Innosights — that used his theory to guide management decisions. He seeded a venture firm, investing in start-ups that had disruptive potential, all the while teaching the most popular MBA electives at the Harvard Business School.

I was in another class when Clay told us about his first meeting with Intel CEO Andy Grove, long before The Innovator’s Dilemma was published. The meeting happened because of an academic paper Clay had written on the hard disk drive industry. Someone at Intel had read it and told Grove to meet Clay. Clay was to tell how Intel could get killed.

“Look, I’ll give you 10 minutes. Explain what you think of Intel.” Grove was gruff, like most of the hard-charging engineers working in the semiconductor sector. “I don’t have time to read academic drivel from people like you.” Clay knew nothing about semiconductors, and certainly not more than Grove. So, instead of telling the CEO what he should do next, Clay said he needed to visualise the theory through another industry. He described how mini-mills had started by making rebar more cheaply than the big mills. The big mills had been happy to be rid of such a low-margin, low-quality product. Then the mini-mills had slowly worked their way upward and killed off the big steel companies.

“All right. I got it,” Grove interrupted. “What you’re telling me, Clay, is that Intel has to go down and stop AMD. We must set up a new business unit, and launch our own low-end competitor.” And that was how Intel launched Celeron Processor — the highest-volume product in the company’s history The lesson? “I would be in deep trouble for telling Andy what to do. I don’t have an opinion,” Clay said. “But I have a theory, and I think my theory has an opinion on Intel. … I teach him how to think.

”In 1997, CEO Grove held up a copy of The Innovator’s Dilemma in front of a packed audience at the Comdex trade show in Las Vegas and proclaimed it the “most important book” he had read in ten years. That same year, Grove gave another keynote address at the annual conference for the Academy of Management, the sort of academic conference only academics would attend eagerly.

He held up Clay’s book and basically said, “I don’t mean to be rude, but there’s nothing any of you have published that’s of use to me except this.” The professors in the audience must have pressed their lips together in tight smiles and held them for a moment before letting them turn into grimaces. They knew Clay had not even succeeded in getting published in any of the A-list journals. It wasn’t a secret. Clay had said so and wasn’t ashamed of it.

So here is an eminent professor whose research Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos had recommended. He had “deeply influenced” Steve Jobs and saved Intel from ruin, and wrote the most downloaded article that Harvard Business Review had ever published. He was ranked the most influential management thinker of our time and gave the world a new way of seeing itself. And yet he never managed to get published in the A-list journals.

The fault line does not seem to be restricted to Clay. Competitive Strategy’s Michael Porter, Blue Ocean’s Kim Chen, Change Masters’ Rosabeth Kanter, and, more recently, Business Model Canvas’s Alex Osterwalder have rarely or never been featured in any A-list journals.

At the same time, outside academia, no manager seems to have heard of the A-list journals: Administrative Science Quarterly, Strategic Management Journal and Academy of Management Review.

This dis-joint, the likes of which have not been seen in the fields of medicine, law, and engineering, has many causes. Whatever the reasons for it, here is its consequence: Smart people are spending their lives trying to answer questions that no one cares about, and when their insights get written, no one reads them.

Not long ago, a friend, who was a tenured professor at a preeminent business school in the Midwest, contemplated changing his job.

He had done all the journal publishing, was in his early 50s, and was secure and comfortable in an institute with a vast endowment. He went and talked to the dean to determine what his next move should be. “You should pick up a hobby,” the dean said. “See, there is this glorious decade lying in front of you. You should just sail into the beautiful sunset, not looking back.”

Not looking back. Maybe that is because many of us live our lives doing things we do not really want to do or neglecting things that are truly important to us. Clay looked back all the time. He was never afraid to reject a good alternative for a better one. He prioritised. He kept teaching his beloved MBA class until he was finally confined to a wheelchair while on treatment for leukemia.

Clay asked the dean for permission to sit in on his own classes, which needed to be taught by other faculty by then. He still wanted to contribute to the discussion in any way that he could. That class remained the most popular elective ever at the Harvard Business School. And so, in the time he had left, Clay would still be seen in his wheelchair every day, led by his wife Christine. He would beat the morning sun to arrive at his office at Morgan Hall and attend to his students. And then, one day, he went on to reside in our hearts.

Originally published on The Edge Singapore

Outlast your competition and thrive in an ever-changing world

In Leap, Howard Yu, LEGO professor of strategy and innovation at IMD, explains how companies can prosper, not just survive. Leap identifies five fundamental principles that allow companies to stay successful in the face of such competition.